Geography of Sudan

Sudan is located in northeastern Africa. It borders the Red Sea between Egypt on the north and Eritrea and Ethiopia on the southeast; it borders Chad and the Central African Republic on the west. It is the largest country in Africa.

Contents |

Land boundaries

The length of Sudan's borders is 7,687 kilometers. Border countries are:

- Central African Republic (1 165 km)

- Chad (1 360 km)

- Democratic Republic of the Congo (628 km)

- Egypt (1 273 km)

- Eritrea (605 km)

- Ethiopia (1 606 km)

- Kenya (234 km)

- Libya (383 km)

- Uganda (435 km) kewl??/

Natural resources

Petroleum is Sudan's major natural resource. The country also has small deposits of chromium ore, [[copper],iron ore, mica, silver, tungsten, and zinc.

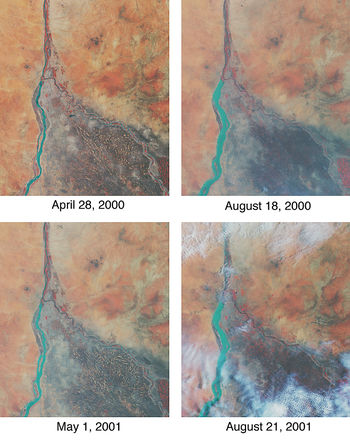

The Nile is the dominant geographic feature of Sudan, flowing 3,000 kilometers from Uganda in the south to Egypt in the north. Most of the country lies within its catchment basin. The Blue Nile and the White Nile, originating in the Ethiopian highlands and the Central African lakes, respectively, join at Khartoum to form the Nile River proper that flows to Egypt. Other major tributaries of the Nile are the Bahr el Ghazal, Sobat, and Atbarah rivers.

Land use

Sudan’s total land area amounts to some 2 510 000 km². About half of this land is suitable for agriculture, of which about 170 000 km² are actually cultivated.

1993 estimates:

- 5% arable land

- 0% permanent crops

- 46% permanent pastures

- 19% forests and woodland

- 30% other areas

- 19 460 km² irrigated land

Environmental issues

Sudan suffers from inadequate supplies of potable water, declining wildlife populations because of warfare and excessive hunting, soil erosion, desertification, and periodic droughts (see Merowe Dam). For example, Sudan historically offered habitat for the endangered Painted Hunting Dog, Lycaon pictus; however. this canid is presently deemed to be extirpated or of very limited population in Sudan, due to the pressures of the human population as well as warfare/genocide.[1]

Geographical regions

Northern Sudan, lying between the Egyptian border and Khartoum, has two distinct parts, the desert and the Nile Valley. To the east of the Nile lies the Nubian Desert; to the west, the Libyan Desert. They are similar—stony, with sandy dunes drifting over the landscape. There is virtually no rainfall in these deserts, and in the Nubian Desert there are no oases. In the west, there are a few small watering holes, such as Bir an Natrun, where the water table reaches the surface to form wells that provide water for nomads, caravans, and administrative patrols, although insufficient to support an oasis and inadequate to provide for a settled population. Flowing through the desert is the Nile Valley, whose alluvial strip of habitable land is no more than two kilometers wide and whose productivity depends on the annual flood.

Western Sudan is a generic term describing the regions known as Darfur and Kurdufan that comprise 850,000 square kilometers. Traditionally, this has been regarded as a single regional unit despite the physical differences. The dominant feature throughout this immense area is the absence of perennial streams; thus, people and animals must remain within reach of permanent wells. Consequently, the population is sparse and unevenly distributed. Western Darfur is an undulating plain dominated by the volcanic massif of Jabal Marrah towering 900 meters above the Sudanic plain; the drainage from Jabal Marrah onto the plain can support a settled population and a variety of wildlife (see East Saharan montane xeric woodlands). Western Darfur stands in contrast to northern and eastern Darfur, which are semidesert with little water either from the intermittent streams known as wadis or from wells that normally go dry during the winter months. Northwest of Darfur and continuing into Chad lies the unusual region called the jizzu, where sporadic winter rains generated from the Mediterranean frequently provide excellent grazing into January or even February. The southern region of western Sudan is known as the qoz, a land of sand dunes that in the rainy season is characterized by a rolling mantle of grass and has more reliable sources of water with its bore holes and hafri (sing., hafr) than does the north. A unique feature of western Sudan is the Nuba mountain range of southeast Kurdufan in the center of the country, a conglomerate of isolated dome-shaped, sugarloaf hills that ascend steeply and abruptly from the great Sudanic plain. Many hills are isolated and extend only a few square kilometers, but there are several large hill masses with internal valleys that cut through the mountains high above the plain.

Sudan's third distinct region is the central clay plains that stretch eastward from the Nuba Mountains to the Ethiopian frontier, broken only by the Ingessana Hills, and from Khartoum in the north to the far reaches of southern Sudan. Between the Dindar and the Rahad rivers, a low ridge slopes down from the Ethiopian highlands to break the endless skyline of the plains, and the occasional hill stands out in stark relief. The central clay plains provide the backbone of Sudan's economy because they are productive where settlements cluster around available water. Furthermore, in the heartland of the central clay plains lies the jazirah, the land between the Blue Nile and the White Nile (literally in Arabic "peninsula") where the great Gezira Scheme (aka Jazirah Scheme) was developed. This project grows cotton for export and has traditionally produced more than half of Sudan's revenue and export earnings.

Northeast of the central clay plains lies eastern Sudan, which is divided between desert and semidesert and includes Al Butanah, the Qash Delta, the Red Sea Hills, and the coastal plain. Al Butanah is an undulating land between Khartoum and Kassala that provides good grazing for cattle, sheep, and goats. East of Al Butanah is a peculiar geological formation known as the Qash Delta. Originally a depression, it has been filled with sand and silt brought down by the flash floods of the Qash River, creating a delta above the surrounding plain. Extending 100 kilometers north of Kassala, the whole area watered by the Qash is a rich grassland with bountiful cultivation long after the river has spent its waters on the surface of its delta. Trees and bushes provide grazing for the camels from the north, and the rich moist soil provides an abundance of food crops and cotton.

Northward beyond the Qash lie the more formidable Red Sea Hills. Dry, bleak, and cooler than the surrounding land, particularly in the heat of the Sudan summer, they stretch northward into Egypt, a jumbled mass of hills where life is hard and unpredictable for the hardy Beja inhabitants. Below the hills sprawls the coastal plain of the Red Sea, varying in width from about fifty-six kilometers in the south near Tawkar to about twenty-four kilometers near the Egyptian frontier. The coastal plain is dry and barren. It consists of rocks, and the seaward side is thick with coral reefs.

The southern clay plains, which can be regarded as an extension of the northern clay plains, extend all the way from northern Sudan to the mountains on the Sudan-Uganda frontier, and in the west from the borders of Central African Republic eastward to the Ethiopian highlands. The plain is covered with swathes of savanna grassland running east to west which have different characteristics depending on the amount of rainfall they receive. These are Sahelian Acacia savanna in the north and East Sudanian savanna to the the south. This great Nilotic plain is broken by several distinctive features. First, the White Nile bisects the plain and provides large permanent water surfaces such as lakes Fajarial, No, and Shambe. Second, As Sudd ("The Sudd"), the world's largest swamp, provides a formidable expanse of lakes, lagoons, and aquatic plants, whose area in high flood waters exceeds 30,000 square kilometers, or approximately the size of Belgium. So intractable was this sudd (see Glossary) as an obstacle to navigation that a passage was not discovered until the mid-nineteenth century. Then as now, As Sudd with its extreme rate of evaporation consumes on average more than half the waters that come down the White Nile from the equatorial lakes. These waters also create a flood plain known as the toic that provides grazing when the flood waters retreat to the permanent swamp and sluggish river, the Bahr al Jabal, as the White Nile is called here.

The land rising to the south and west of the southern clay plain is referred to as the Ironstone Plateau (Jabal Hadid), a name derived from its laterite soils and increasing elevation. The plateau rises from the west bank of the Nile, sloping gradually upward to the Congo-Nile watershed. The land is well watered, providing rich cultivation, but the streams and rivers that come down from the watershed divide and erode the land before flowing on to the Nilotic plain flow into in As Sudd. Along the streams of this Northern Congolian forest-savanna mosaic are gallery forests, the beginnings of the tropical rain forests that extend far into Zaire. To the east of the Jabal Hadid and the Bahr al Jabal rise the foothills of the mountain ranges along the Sudan-Uganda border — the Imatong, Didinga, and Dongotona — which rise to more than 3,000 meters. These mountains form a contrast to the great plains to the north that dominate Sudan's geography.

Sudan includes islands located in the Nile (including Aba Island, Badien Island, Sai Island, and, at the confluence of the Blue and White Nile, Tuti Island) and in the Red Sea (including the Suakin Archipelago).

Soils

The country's soils can be divided geographically into three categories. These are the sandy soils of the northern and west central areas, the clay soils of the central region, and the laterite soils of the south. Less extensive and widely separated, but of major economic importance, is a fourth group consisting of alluvial soils found along the lower reaches of the White Nile and Blue Nile rivers, along the main Nile to Lake Nubia, in the delta of the Qash River in the Kassala area, and in the Baraka Delta in the area of Tawkar near the Red Sea in Ash Sharqi State.

Agriculturally, the most important soils are the clays in central Sudan that extend from west of Kassala through Al Awsat and southern Kurdufan. Known as cracking soils because of the practice of allowing them to dry out and crack during the dry months to restore their permeability, they are used in the areas of Al Jazirah and Khashm al Qirbah for irrigated cultivation. East of the Blue Nile, large areas are used for mechanized rainfed crops. West of the White Nile, these soils are used by traditional cultivators to grow sorghum, sesame, peanuts, and (in the area around the Nuba Mountains) cotton. The southern part of the clay soil zone lies in the broad floodplain of the upper reaches of the White Nile and its tributaries, covering most of Aali an Nil and upper Bahr al Ghazal states. Subject to heavy rainfall during the rainy season, the floodplain proper is inundated for four to six months — a large swampy area, As Sudd, is permanently flooded — and adjacent areas are flooded for one or two months. In general this area is poorly suited to crop production, but the grasses it supports during dry periods are used for grazing.

The sandy soils in the semiarid areas south of the desert in northern Kurdufan and northern Darfur states support vegetation used for grazing. In the southern part of these states and the western part of southern Darfur are the so-called qoz sands. Livestock raising is this area's major activity, but a significant amount of crop cultivation, mainly of pearl millet, also occurs. Peanuts and sesame are grown as cash crops. The qoz sands are the principal area from which gum arabic is obtained through tapping of Acacia senegal (known locally as hashab). This tree grows readily in the region, and cultivators occasionally plant hashab trees when land is returned to fallow.

The laterite soils of the south cover most of western Al Istiwai and Bahr al Ghazal states. They underlie the extensive moist woodlands found in these provinces. Crop production is scattered, and the soils, where cultivated, lose fertility relatively quickly; even the richer soils are usually returned to bush fallow within five years.

Climate

Although Sudan lies within the tropics, the climate ranges from arid in the north to tropical wet-and-dry in the far southwest. Temperatures do not vary greatly with the season at any location; the most significant climatic variables are rainfall and the length of the dry season. Variations in the length of the dry season depend on which of two air flows predominates, dry northeasterly winds from the Arabian Peninsula or moist southwesterly winds from the Congo River basin.

From January to March, the country is under the influence of the dry northeasterlies. There is practically no rainfall countrywide except for a small area in northwestern Sudan in where the winds have passed over the Mediterranean bringing occasional light rains. By early April, the moist southwesterlies have reached southern Sudan, bringing heavy rains and thunderstorms. By July the moist air has reached Khartoum, and in August it extends to its usual northern limits around Abu Hamad, although in some years the humid air may even reach the Egyptian border. The flow becomes weaker as it spreads north. In September the dry northeasterlies begin to strengthen and to push south and by the end of December they cover the entire country. Yambio, close to the border with Zaire, has a nine-month rainy season (April-December) and receives an average of 1,142 millimeters (45.0 in) of rain each year; Khartoum has a three-month rainy season (July-September) with an annual average rainfall of 161 millimeters (6.3 in); Atbarah receives showers in August that produce an annual average of only 74 millimeters (2.9 in).

In some years, the arrival of the southwesterlies and their rain in central Sudan can be delayed, or they may not come at all. If that happens, drought and famine follow. The decades of the 1970s and 1980s saw the southwesterlies frequently fail, with disastrous results for the Sudanese people and economy.

Temperatures are highest at the end of the dry season when cloudless skies and dry air allow them to soar. The far south, however, with only a short dry season, has uniformly high temperatures throughout the year. In Khartoum, the warmest months are May and June, when average highs are 41 °C (105.8 °F) and temperatures can reach 48 °C (118.4 °F). Northern Sudan, with its short rainy season, has hot daytime temperatures year round, except for winter months in the northwest where there is precipitation from the Mediterranean in January and February. Conditions in highland areas are generally cooler, and the hot daytime temperatures during the dry season throughout central and northern Sudan fall rapidly after sunset. Lows in Khartoum average 15 °C (59 °F) in January and have dropped as low as 6 °C (42.8 °F) after the passing of a cool front in winter.

The haboob, a violent dust storm, can occur in central Sudan when the moist southwesterly flow first arrives (May through July). The moist, unstable air forms thunderstorms in the heat of the afternoon. The initial downflow of air from an approaching storm produces a huge yellow wall of sand and clay that can temporarily reduce visibility to zero.

See also

- States of Sudanpiepiepiepie

References

- Richard Pankhurst. 1997. The Ethiopian Borderlands (Lawrenceville: Red Sea Press

- C. Michael Hogan. 2009. Painted Hunting Dog: Lycaon pictus, GlobalTwitcher.com, ed. N. Stromberg

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the Library of Congress Country Studies.

Line notes

- ↑ C. Michael Hogan. 2009

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

|||||||||||